|

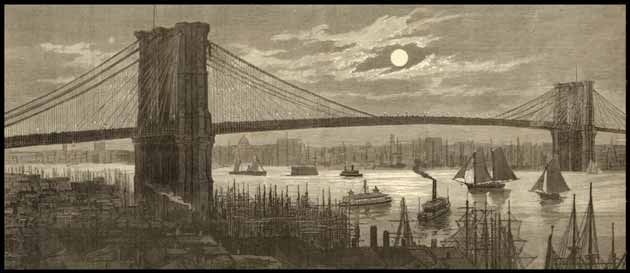

Technological Transformations New modes of transportation expanded the livable and workable city, and New York gradually spread outwards. The Rapid Transit Act (1875) granted railway construction franchises to private businesses, which greatly expanded the number of tracks traversing the city, both on the ground and elevated above ground. Travel from upper Manhattan and the Bronx–half of which had been annexed by the city in 1874–became much easier. The Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883, and by 1885 a cable car had been installed to swiftly connect commuters from Brooklyn's own railroad system to that of Manhattan's. Brooklyn and Queens would remain cities unto themselves until the consolidation of the "five boroughs" in 1898, but advances in transit forged more intimate connections between New York City and its immediate neighbors north, south and east.

New technologies enabled the city to build both upwards and downwards in the 1880s. Expensive land prices combined with business demand for increased space in and around the bustling downtown financial district. Firms soon realized that the best and most convenient space was right above their heads. Advances in architecture, inspired by the arrival from France and completion in 1886 of Gustave Eiffel's one hundred fifty one-foot Statue of Liberty, ensured that tall, thin buildings could withstand significant wind force. Soon, buildings reaching ten stories dotted lower Manhattan, and, in 1890, Joseph Pulitzer's newspaper, the New York World, began operating out of the World Tower, which was then the world's largest building at just over three hundred feet.

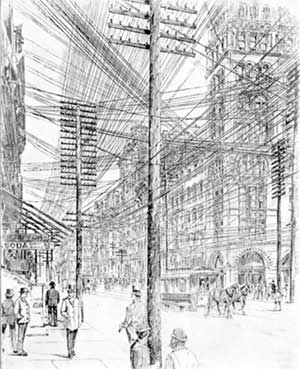

The densely populated and fully developed lower

part of the city made the delivery of goods and services such

as power, water, and steam for heat difficult and, as the city

grew skyward, it grew in the opposite direction as well. In 1882,

Thomas Edison illuminated nearly forty businesses in southern

Manhattan with eight hundred incandescent lamps fed by subterranean

electrical wiring running through approximately fifteen miles

of tunnels and powered by several large generators housed on Pearl

Street. Steam heat was also delivered to New York's business district through underground piping connected to central boiler plants. But as the rest of the city became wired–for telegraph, for telephone, and for power–companies such as Western Union, Bell Telephone, the Gold and Stock Ticker, as well as the city's police and fire departments, implanted a vast array of poles in the streets of New York City. These poles soared ninety feet into the sky, held up to twenty-four crossties, each of which carried up to twenty wires. The city government grew increasingly concerned about this excessive wiring: electrical wires often snapped, fell to the ground, and sent sparks flying towards the city's citizens, homes, and businesses. In 1884, encouraged by the success of Edison's subterranean project, the New York State Legislature ordered that all electrical and communication wires were to be buried underground. However, in the absence of strict enforcement and the high costs of insulating buried wires, New York businesses, for the most part, ignored the order. |