|

The Blizzard of 1888 On the morning of Saturday, March 10, 1888, a low pressure weather system extending from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico moved eastward across the country's midsection at high speed. It contained two storms: a southern one dumping rain on St. Louis and a northern one dropping snow on Green Bay, Wisconsin. By the evening of the tenth, the southern storm system was moving out to sea over the Carolinas, and the northern storm system seemed to be phasing out. The weather in New York City on that day was seasonably warm: it was sunny and in the upper fifties. The forecast for New York City and much of the Northeast for Sunday, March 11, predicted southeasterly winds, a slightly warmer temperature, and rain in the evening

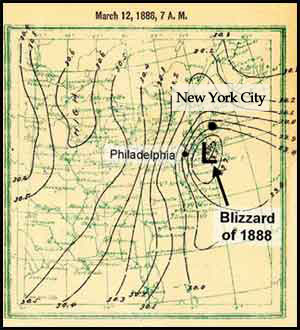

The forecast was, for the most part, correct. But late in the day the southern storm system turned from its northeasterly course and began moving directly north, up the Atlantic coast. As the storm moved, the wind shifted from the southeast to the north and then to the northeast, and the mixture of increasingly cold air with the warm ocean water the storm picked up were disastrous. The force of the developing hurricane crashed thirty-five ships into one another at the mouth of the Delaware Bay. Rain did indeed come to New York City, but late on Sunday evening it switched to hail, to sleet, and then, just after midnight, to a wind-driven snow. By 7 a.m. on the morning of Monday, March 12, the temperature had dropped to single digits and ten inches of snow were on the ground. Over the course of the next day and a half, another eleven inches of snow would fall. New York City was unprepared for a storm of this magnitude. New Yorkers were initially unaware of the severity of the blizzard, and many workers who left for jobs early in the morning ended up stranded en route. A powerful wind, gusting up to eighty miles per hour and averaging thirty five, piled snowdrifts that in some places reached the second stories of buildings, and pushed a bitter cold through the streets that stopped horses in their tracks. Ice clogged the East River; in the absence of ferry service hundreds of pedestrians risked their lives by crossing the frozen river on foot from Brooklyn. Trains entering and leaving the city were also rendered immobile by the wind gusts and snow piles, and ice on the tracks of the elevated commuter trains caused several accidents in upper Manhattan, killing one and injuring dozens. Over two hundred New Yorkers died as a result of the storm, either from accidents, from freezing to death, or because they were unable to get food or medical attention. The storm affected all classes of citizens, each of whom responded in their own ways: wealthy New Yorkers were able to stay inside and could afford plentiful coal to warm their homes , while working-class New Yorkers looked for ways to augment their incomes by shoveling out and helping their stranded fellow-citizens during the storm. The Blizzard of 1888 paralyzed New York City, along with the entire Northeast, for two days; it would take more than another week for the city to fully dig out and get back to normal. Contemporary estimates put the cost of the blizzard to New York's businesses at more than $20 million.

As with many other New York disasters, New Yorkers became aware during the course of the blizzard that they were in the midst of an historic event. They witnessed familiar streets turn into something more exotic, and many New Yorkers–those not fighting for their lives–experienced the blizzard with a kind of giddy excitement. The blizzard knocked down power and telephone lines, stranded travelers and commuters, and made communication with the rest of the country next to impossible. The most significant weather disaster in New York City history, the Blizzard of 1888 has long stood out in the city's history and memory as both an unprecedented natural disaster and as an example of how New Yorkers have used disasters to propel material progress and technological transformation. In the blizzard's aftermath, New Yorkers redoubled their commitment to use technological advancements to ease the burden such natural disasters placed on the city– within a few shorts years after the blizzard the city's electrical and telegraph wires were buried underground, while the storm fostered demand for building an underground transportation system. |